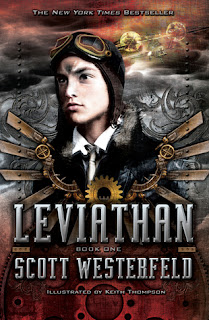

Release Date: Oct. 6, 2009Hello, readers! Since a general reading slump and the holidays have combined to put me already almost a month behind in getting this review out, let’s just jump right in to my thoughts on Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan.

Publisher: Simon Pulse

Age Group: Young Adult

Format: E-book

Source: Purchased

Pages: 448

Buy: Amazon / Barnes & Noble / Google

Description: Goodreads

It is the cusp of World War I, and all the European powers are arming up. The Austro-Hungarians and Germans have their Clankers, steam-driven iron machines loaded with guns and ammunition. The British Darwinists employ fabricated animals as their weaponry. Their Leviathan is a whale airship, and the most masterful beast in the British fleet.

Aleksandar Ferdinand, prince of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, is on the run. His own people have turned on him. His title is worthless. All he has is a battle-torn Stormwalker and a loyal crew of men.

Deryn Sharp is a commoner, a girl disguised as a boy in the British Air Service. She's a brilliant airman. But her secret is in constant danger of being discovered.

With the Great War brewing, Alek's and Deryn's paths cross in the most unexpected way...taking them both aboard the Leviathan on a fantastical, around-the-world adventure. One that will change both their lives forever.

There are a lot of things to like about the novel’s style, not the least of which is the shift in voice depending on which character the chapter is focused on. The dichotomy is most obvious in Deryn’s chapters simply because the entire vocabulary shifts. Alek’s chapters are written in a rather standard style while Deryn’s are littered with Darwinist words and phrases, such as all fabrications being referred to as “beasties.” As a result, her chapters always seem a bit more fun, which works well since everything is an adventure for her, while Alek only has the weight of the whole world on his shoulders.

The novel is also filled with tiny touches that show just how much thought and detail Westerfeld put into it, such as shifting units of measure between metric and imperial systems depending on the chapter, which also leads to a somewhat funny exchange where both sides are converting into each others’ units and back again as they try to work out an exchange. Westerfeld also employs one of my favorite tricks to let language sound normal without veering off into Parental Advisory territory: simply replacing a curse word with something else. It’s a simple trick, but it’s so much better than having people say, “Oh, shucks,” as things are exploding around them.

On a few occasions, Westerfeld has characters react to and understand the other side’s technology in terms of their own, such as Alek thinking that the Darwinist’s war birds are swooping like fighter planes. It seems like a simple enough trick, but it’s the kind of believable touch that shows care and really rounds out a world or a character.

While there quite a few clever stylistic touches, there are a few stylistic niggles as well. Most of these problems exist in a large number of books and movies and it doesn’t seem fair to take Westerfeld to task for them. That said, there is one stylistic thing I couldn’t figure out: Why the point of view changes every other chapter. It would make sense if it switched every chapter, but having two chapters in a row for each character seemed like an odd choice. I couldn’t figure out why they weren’t just combine into one chapter. Maybe there’s not a reason for it, but in that case it seems like an even weirder choice.

As far as the technology is concerned, I’m going to talk mostly about the Darwinist fabrications both because they’re were most of the creative ideas lie and because giant robots are always cool. Nothing else needs to be said. Each of the fabs seemed quite well thought out and it was fun seeing what combination of form and function Westerfeld was going to throw at me next. The vision of the Leviathan as an entire ecosystem rather than a single creature was particularly inspired.

Westerfeld seems to know exactly how each piece of his imagined technology works, even if he doesn’t tell us. He also does an excellent job at introducing both side of the tech gradually and without exposition. For instance, fabs are mentioned as Deryn passes a few early in the novel, then she rides in a flying one, and then this massive, flying ecosystem is introduced. There’s no giant info dump, just a slow introduction designed so each new bit of technology seems like a logical extension of what we’ve already seen.

Perhaps surprisingly, I don’t have any huge gripes with the Darwinist technology. One of the few issues I had originally was that using something filled with hydrogen, which could explode as a result of a stray bullet, seemed like a really stupid idea. Then Westerfeld reminded me that the Germans used zepplins during the real First World War. That said, I do have two minor issues with the tech. First, it seems to me that you wouldn’t really want war machines that could decide not to work because they get nervous. If I fire a gun or a missile, it would be nice for it to actually move in the general direction in which I pointed it, rather than it getting scared because there’s a thunderstorm.

Upon further reflection, though, actual real-world Clanker-esque tech wasn’t always the most reliable thing at the time, either, and you could probably convince me that the cheap production and maintenance might be worth the trade. My other complaint is more thematic in nature and is similar to my style complaint: I’m not sure what the point is. I thought originally that the differing technologies were supposed to be some sort of nature vs. science struggle, but the fabs only exist because scientists screwed with nature, so that seems out. Maybe it’s supposed to be something as disappointingly simplistic as our protagonists overcoming their deep philosophical differences. Maybe there isn’t supposed to be a thematic point. Maybe it’s just supposed to be cool, which is a completely fine answer.

As far as the main characters go, I found Deryn to be far more interesting than Alek. Alek feels like little more than a plot device, despite some lip service being given to a few interesting ideas. For instance, there’s a moment where it’s revealed that Alek, despite being able to speak many languages, can’t even read the local paper his would-be subjects read because he doesn’t understand their language. The divide between rulers and their subjects could have come into play in some interesting ways, but instead it’s never mentioned again.

On the other hand, Deryn is interesting not only because she’s our window into the Darwinist tech, but also because Westerfeld handles her attempts to pass as a boy quite well. He smartly writes out the possibility of her being discovered based simply on physical traits, instead putting the focus on her need to behave like a boy by, for instance, checking her nails by curling her fingers instead of splaying them. He also doesn’t belabor the point by having her get almost-discovered every few chapters. In fact, she doesn’t really even come close to being discovered. Somehow, Westerfeld managed to turn what I thought was going to be the most annoying part of the book into one of its strengths.

As this review is already getting pretty long, I don’t have too much to say about the plot. I enjoyed the book just fine when I was reading it. The action is well written, the pace is good, and at least a few of the characters are fun to spend time with. There are also some really well-written, spy-gamey exchanges among the characters where they’re each trying to pry information out of each other while not giving up any themselves. That said, when I finished the book, I didn’t really feel like anything important happened. The Leviathan still flies. Alek is still on the run, just not in his ice fortress. About all that actually happened was that our characters met and, apparently, will be parting ways. Rather than feeling actually dire or epic, the weight of the actual conflict driving all of the action comes because I know about the actual, real-world World War I, not because of anything the novel itself did. In the end, it felt a lot like a popcorn action flick: Fun while it lasted, but not much more than that.

No comments:

Post a Comment